Are You a Boy or a Girl? Pt. II

My magic trick

Self-Portrait III: My Magic Trick, 2025. Mixed-media collage with encaustic wax finish on wood panel, 25” x 25” x 1 1/2”. Prints available.

That humiliating incident in the library at the beginning of seventh grade (see Part I) delivered a message that I heard loud and clear: I lived in a world that rejected my masculine side. So I started making more of an effort to look like a girl.

I started emulating my new friends by wearing lip gloss and skirts. I spent time at the beach bronzing my skin and lightening my hair. Becoming pretty was like any of the other sports I was actively involved in, something I could practice and perform to compete more effectively in this age-old, covert game of female against female.

During that first year of middle school, however, I was still a competitive gymnast, a catcher on a softball team, and a goalie in league soccer, and I was strongly bonded with the girls on my teams. Sports, my teammates, and getting good grades had been at the center of my life, so adopting a new persona was going to take some time.

Me on the right with my best friend, Crystal. As you might guess, our parents had difficulty distinguishing us in our competition photos. (1981)

***

Middle school is a bardo—an in-between time of transitions and transformations. Big changes are the rule, not the exception. This isn’t anything unique for most girls (and boys), but for some, this societal rite of passage from the innocent, androgynous child to a role-playing adolescent being molded to serve society is made more difficult, and sometimes traumatic, by emotional neglect and abuse at home.

As happy and normal as I had seemed in elementary school, there were cracks in my psychological foundation that began slowly revealing themselves in subtle ways, as relationships and the social fabric of my life started taking on new contours and complexities.

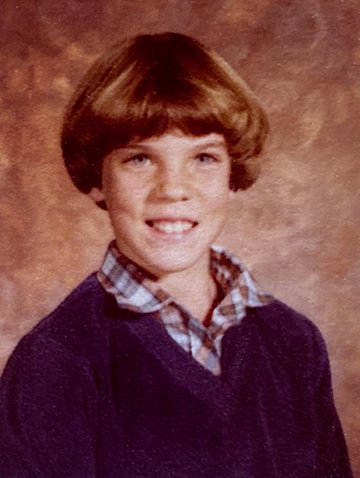

Fifth-grade school photo. (1980)

By the time I was in middle school, I’d already begun to feel rejected and overwhelmed by a world that didn’t want my masculinity or androgyny. This was made all the more bewildering because after my parents split up when I was two, I had been abandoned by my father, my role model of masculinity.

All of the energy I had for life, and my confidence to achieve the things I wanted and imagined I could do, started to get repressed behind the new facade I was building, that of a nice, good, pretty girl who acquiesced to the needs, desires, and preferences of others, rather than asserting my own. By the time I was sixteen, those original, healthy masculine impulses became bound in guilt and shame and started to come through my behavior in exaggerated, convoluted, and misplaced ways.

Bound, 2020, Mixed-media collage on 4 × 6 index card, an early collage sketch. It was made to be the Five of Pentacles for my handmade Neuro-Tarot deck (still a work-in-progress).

The absence of my father during my formative years, my mother’s undiagnosed PTSD and bipolar personality, childhood sexual abuse (at the hands of a stranger when I was 3yo and my step-grandfather when I was 7yo), and our society’s insistence on casting people into rigid roles and identities, all helped to create a psychological recipe that silently transmuted the healthy needs of my inner masculine into an increasingly aggressive need for attention from others, perfectionism, certainty, and control — all expressions of the wounded masculine.

Carol’s question about my gender had been a painful initiation into adolescence. I was encountering an unsafe world that required defensive solutions to the growing problem of my unattractive boyishness. Thankfully, there were places we could go to learn about being a proper, attractive woman. When my mother suggested I enroll in modeling school, I was a porous sponge waiting to absorb a new foundation for life.

My “before” picture at the John Robert Powers Modeling School & Agency. (1983)

The first step at the John Robert Powers Modeling School was to take a photo of my face with my hair pulled back to reveal its full shape, and it was determined that mine was a combination of rectangular, oval, and triangular. (Is that even possible?) This would determine the angle at which to apply my concealer and blush.

As I listened to the beauty consultant, I gathered that having a combination-shaped face must be undesirable; otherwise, why would it need to be hidden, changed, or concealed? I was both exceedingly uncomfortable and hopeful about the prospects of fixing my appearance as I watched and listened to the beauty expert reveal her master plan for my new-and-improved “look,” which had been drawn on a piece of tissue paper and overlayed on the photo of my un-groomed face.

***

Eighth-grade graduation day. (1984)

The “new look” and social programming did its job: I started getting praise for my appearance. I was encouraged and rewarded for looking more attractive and feminine, and along the way, I learned to push down the shame and insecurity and enjoy the attention and power it gave me.

As my friend Richard put it to me one afternoon on the curb in front of my house where I used to play catch in the street with Jason, “you’re moving up the ‘hotness’ scale and guys are noticing.”

Just a few years before, I was a plain, boyish, and buck-toothed kid who never got attention for my appearance — not the kind a skinny tomboy with six-pack abs and a bad Dorothy Hamill haircut would want, anyway.

But in that moment, Richard, like a magician, cast a new spell over me.

His words created a new reality, one in which I was “hot”! It didn’t matter if it was true; he said it, I believed it, and it gave me newfound happiness. My life as a “pretty girl” had begun.

High school graduation day. (1988)

Being left to soothe my emerging insecurities by seeking external validation (rather than going into family therapy, which is what we all truly needed), I was unwittingly offering myself as prey to the beauty industry and men’s desires. Seeking ever-more attention, I began looking at myself through a lens of female hotness and “fuckability,” as my culture osmotically encouraged me to do.

If I hadn’t wanted the attention, I’d have been better off remaining a wallflower, but I liked the attention; in fact, I craved it.

But I didn’t know what to do with it. I was emotionally unprepared to deal with sexual attention. What I really craved was my father and mother’s safe, loving, and consistent attention and mirroring, but that wasn’t forthcoming, so a substitute was better than nothing.

I didn’t know it then, but my mother’s behavior was characteristic of a bipolar condition. She would habitually give me love, then snatch it away with bitter disapproval, leaving me reeling from the emotional rollercoaster. Attention from boys was a salve of sorts, not to mention a place to project my abandonment issues with my father.

Self-Portrait IV: The Two of Me, 2025. Mixed-media collage with encaustic wax finish on wood panel, 19” x 19” x 1 1/2”. Prints available.

To maintain control of this newly crafted identity (and the unmet emotional needs building volcanic force beneath my quiet, “hot” facade) I needed to fortify myself by drawing strong external boundaries, but I didn’t yet know how to do that. Instead, my unconscious reaction was to put up rigid internal walls around my heart and the essential me, until all anyone saw was the “me” I had constructed.

This “masking” process, whereby some of us put up such strong walls around our vulnerabilities that we quite literally disconnect ourselves from ourselves, acts as a protective shield.

The sexual attention of males had started my transformation, but I was the one who was turning myself into a sex object. This was becoming my magic trick now.

Being seen as sexually attractive to guys was quickly becoming a type of armor, something I could wield as a superpower; I could get attention and remain hidden at the same time. In essence, I’d made a “pretty girl” mask, and thus began my courtship with the archetype of the femme fatale.

Self-Portrait V: Femme Fatale Rising, 2025, 17” x 18.5” x 1 1/2”. Prints available.

The third (and final) essay in this series is about the inner split we create when we make masks, and the dance we do with the devil when we try to re-create ourselves from the discarded remains of our natural selves and impulses.

Up next on The Seeker’s Notebook — “Are You a Boy or a Girl? Part III: Was I becoming a femme fatale?